More research urged before scaling ocean carbon capture as UK trial abandoned

Scientists from the University of Exeter and Plymouth Marine Laboratory in the UK are urging caution over large-scale deployment of ocean carbon removal technologies, noting that major gaps remain in understanding their ecological impacts.

This warning follows a comprehensive review under the SeaCURE project – one of the first full-scale assessments of direct ocean carbon capture and storage (DOCCS) systems.

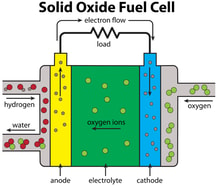

SeaCURE’s electrochemical process removes dissolved inorganic carbon from seawater, raising the pH before returning the treated water to the ocean, which allows it to absorb more atmospheric carbon dioxide.

“It would be irresponsible to deploy DOCCS technology at commercial scales until we can more accurately understand how species and ecosystems will react,” said lead author Guy Hooper. He added that returning high‑pH water without sufficient dilution “could place stress on certain marine organisms.”

Co-author Helen Findlay described the approach as “potentially very exciting,” but highlighted that “environmental research must keep pace with technological development.”

This comes just months after Canadian company Planetary Technologies abandoned its ocean alkalinity enhancement trialin Cornwall. It aimed to disperse magnesium hydroxide via a wastewater outfall to boost seawater alkalinity and CO2 uptake. Though the UK Environment Agency found very low ecological risk at pilot scale, the project stalled due to difficulties in sourcing a sustainable mineral supply.

A trial in St Ives, Cornwall that aimed to remove CO2 from the oceans was scrapped earlier this year after environmental concerns ©Shutterstock

Both initiatives aim to strengthen the ocean’s ability to absorb CO2 but in very different ways. SeaCURE actively electrochemically extracts carbon and requires careful dilution of treated effluent, whereas the St Ives Bay trial relied on passive chemical enhancement through mineral addition.

Other global efforts worth noting

In Singapore, a $20m project backed by Equatic and UCLA’s Institute for Carbon Management is building the world’s largest ocean-based carbon removal plant. It’s expected to remove approximately 3,650 tonnes of CO2 annually using electrolysis, while generating carbon-negative hydrogen at PUB’s research facility in Tuas.

In the US, Hawaii hosts a pilot by Captura (supported by the Department of Energy and Equinor) that employs electrodialysis to pull CO2 from seawater. This initiative is aiming for removal rates of about 1,000 tonnes annually.

A separate project at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution seeks to test ocean alkalinity enhancement under an EPA permitting process, an early step toward understanding regulatory frameworks for marine-based carbon removal.

As the Exeter review makes clear, scaling these technologies safely and effectively hinges on closing critical knowledge gaps and delivering both environmental assurances and commercial feasibility.