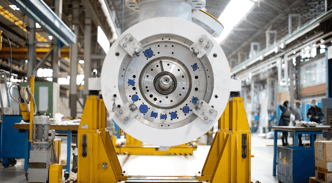

Project Tundra targets world’s largest CCUS power plant

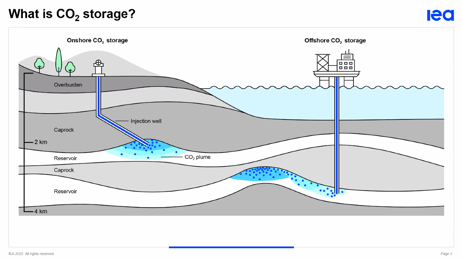

Minnkota Power Cooperative plans to retrofit the Milton R. Young coal-powered power plant and turn it into the largest carbon capture facility of its kind.

The local utility, aiming to raise the $1bn the project requires, is targeting more than 90% capture of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the plant’s 455MW unit.

David Greeson, a Consultant on Project Tundra said: “The company is committed to finding a way to do something about carbon dioxide emissions, and that’s why they’re spending the money to develop this project.”

The majority of coal-fired plants in the US are reaching middle age. The Young station embodies 1970s technology, which makes upgrading these vintage plants with CCS a costly proposition.

... to continue reading you must be subscribed